Insights from Malawi’s Deep Dive of the Integrated Disease Surveillance System

Daily life at Lake Malawi

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on the world revealing significant weaknesses and gaps in our health systems. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the importance of robust and well-functioning surveillance systems given how essential they are to local decision-making and global information sharing. A country’s capacity to collect, compile, diagnose, monitor, and analyze data is the foundation of an effective surveillance system that enables countries to plan and take necessary control measures.

Moreover, an integrated disease surveillance (IDS) strategy optimizes the use of resources by integrating, standardizing, and coordinating information from various surveillance systems, registries, and other data sources, and facilitating reporting and promoting data use by decision-makers.

Like a majority of African countries, Malawi has adopted the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) strategy developed by the World Health Organization's Regional Office for Africa as its national surveillance system. In Malawi, the implementation of the IDSR strategy is supervised by the Public Health Institute of Malawi (PHIM).

IANPHI received funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to conduct a study of IDS around the world. The aim of the study was to examine the status of national surveillance systems, the extent to which IDS systems have been developed and operationalized, and the evidence base for the effectiveness of IDS.

In sum, the aims of the work were to:

- Document the current state of knowledge, evidence for, and understanding of IDS

- Describe the state of IDS across the IANPHI network, mapping variations in definitions, approaches, and implementation of IDS

- Identify the barriers, enablers, and opportunities for IDS development and implementation, considering some of the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study entailed a systematic scoping review, a survey of IANPHI member National Public Health Institutes (NPHIs), and seven case studies (i.e., deep dives). The deep dive workstream specifically engaged NPHIs and was conducted in three high-income countries and four lower-middle income countries to better understand strengths, weaknesses, and challenges on the ground. To facilitate the process, deep dives were conducted jointly by two NPHIs using a twinning approach.

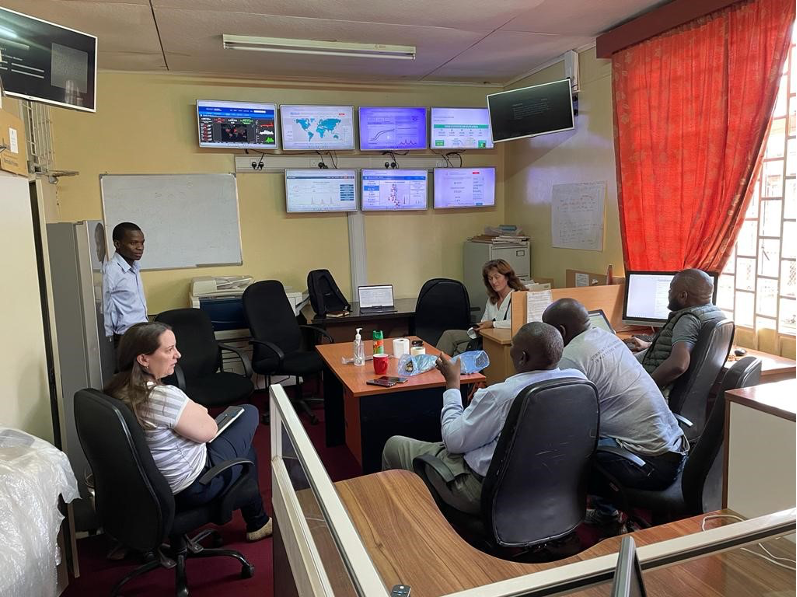

Meeting in the Emergency Operations Center (EOC), a room that is open 24/7

Deep Dive in Malawi

The Public Health Institute of Malawi (PHIM) and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) have had a close collaboration for many years. Since 2008, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) has been engaged in a long-term collaboration with PHIM and supported its establishment in 2013. The two institutes have a similar role when it comes to surveillance of infectious diseases in their respective countries, but very different resources to do so. One of the areas of collaboration request by PHIM was IDSR, for which the institute is responsible.

Beginning in May 2022, the two institutes started collaborating on an IDS deep dive study to document the status of Malawi’s IDS system, assess PHIM's role in the implementation of IDS, identify ongoing challenges and gaps, and provide recommendations for improvement. The collaboration between the two institutes was already ongoing when the opportunity of joining the IANPHI initiative came up, and Malawi asked to become one of the countries to do the IANPHI “deep dive” exercise.

IDS deep dive highlighted the challenge of integrating data from the vertical programs into the IDSR. With continued support from our partners to strengthen disease surveillance, there is hope that full integration can be reached.

The Malawi Deep Dive team consisted of Dr. Benson Chilima, director of PHIM, as well as PHIM colleagues, Dr. Annie Chauma, Ms. Mtisunge Yelewa, Mr. Noel Khanga, Dr. Dzinkambane Kambalame, and Mr. Edward Chado. The NIPH team included Dr. Bjørn Iversen, Dr. Trude Arnesen, Ms. Emily MacDonald, and Dr. Karine Nordstrand. Together, the teams conducted a mapping exercise in May 2023 and later followed up with data collection efforts that were completed in August. Ms. Mtisunge Yelewa and Dr. Arnesen were present throughout all activities, while the others participated in different parts.

The deep dive consisted of collecting and reviewing relevant documents (i.e., strategies, evaluations, and action plans for health security), meeting with stakeholders, and conducting six focus groups and nine key informant interviews. The six focus groups involved two primary health care facilities, two district health offices, and two focused on national level stakeholders including the Ministry of Health (MoH), donors, and international organizations.

IDSR site visit in Malawi with NPHI representatives and staff at Health Center Area 25

Deep Dive Key Findings

Findings from the deep dive highlight several key areas. In terms of governance, the deep dive revealed that while the MoH oversees the Health Management Information System (HMIS), PHIM plays a central role in Malawi’s surveillance activities. Malawi also uses the third edition of the Technical Guidelines for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) in the African Region. Aside from HMIS and IDSR, data is also collected by several vertical disease programs (e.g., HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and schistosomiasis) that are run by donor organizations (i.e., PEPFAR, Global Fund, World Bank). In addition, there is a One Health Surveillance Platform (OHSP), an integrated community HIS (ICHIS), and an eIDSR, underscoring the complexity of Malawi’s data surveillance landscape.

Funding was an issue raised by several stakeholders. In contrast to vertical disease programs that receive substantial financing support, funding for IDSR is much weaker. Respondents noted that funds and poor data quality are often closely related. Poor data quality, for example, can be attributed to a lack of funding for supervision, training, and tools. Availability of digital equipment, capacity of electronic data transfer, and server capacity may also affect quality. Data quality can be further compromised by unclear case definitions and illegible diagnostic codes.

The burden of reporting was another prominent issue. Some respondents indicated that they are required to prepare more than 40 reports each month thus illustrating the time, waste, and inefficiencies of parallel reporting mechanisms. The need for clear guidelines and improved laboratory systems was also mentioned by participants.

During the IDS deep dive, we discovered that many reportable diseases are not well understood by those who report them. This prompted us to have second thoughts about the priority conditions under surveillance and the team agreed to remove some from the list.

The findings from the deep dive revealed several areas for improvement such as:

- Reporting: Improve the IDSR guidelines so that the case definitions for the conditions monitored are understandable and accessible; revise list of diseases reported from the districts to include only those that can be diagnosed at that level

- Training: provide training for those who complete reports, including data clerks

- Connectivity: improve internet connectivity or access to the internet to enable reporting

- Data integration: integrate information from different vertical disease programs with the IDSR to improve data quality and reduce work

- Task force: establish a national task force to integrate information from different programs and IDSR

- Laboratory reporting: strengthen the laboratory system given that it is the backbone of disease surveillance

- Feedback: provide feedback to those reporting the data so they can use it for decision making and planning

- Data validation: validate data in the reporting chain with quality checks at the district level

- Technical challenges: address unreliable internet connectivity and insufficient server capacity.

Findings from the deep dive highlight the need for a comprehensive approach to improve the reporting process, including revisions to the reporting tools, training, improved connectivity, the integration of data from different programs, strengthened laboratory reporting, and providing feedback to those who report.

Recommendations from Malawi's Deep Dive

Two main recommendations emerged from the IDS deep dive findings: 1) integrate national surveillance systems and 2) improve data quality. To achieve these, the following actions are recommended:

- Improve data quality at the facility level by making case definitions available as posters and pocketbooks, writing out abbreviations and acronyms, and orienting data clerks on correct disease codes

- Establish a formal collaboration between vertical programs to promote integration and understanding. This collaboration should ensure agreement on common case definitions, reporting frequencies, a single data input from a reporting facility, and improved interoperability of laboratory data with DHIS2/OHSP

- Align the list of reportable diseases with the reporting forms including how often reporting is conducted (i.e., immediate, weekly, monthly, and quarterly)

- Improve data quality by assigning focal persons at district and national levels to validate data reports.

Data clerk at the Kawale Health Centre with an array of forms that need to be completed

Findings from the Malawi Deep Dive study were first presented to the MoH in a conference in Lilongwe. As part of the follow-up, PHIM, supported by NIPH, held a seminar to revise the list of notifiable diseases and the case definitions. Dr. Chilima presented the main findings at an IANPHI pre-meeting to the World Health Summit in Berlin in October 2022. Many challenges emerged from the Deep Dive, so PHIM and the MoH will continue to make strides in implementing the key recommendations. In addition, the PhD candidate in the PHIM-NIPH project has taken up the challenge to explore it further.

Together, PHIM and NIPH concluded that gaps in IDS implementation may be addressed by strengthening coordination and collaboration among stakeholders, increasing funding, and improving the use of technology. In sum, findings from Malawi’s IDS deep dive study provide valuable insights for other countries struggling with similar data and reporting issues. The study recommendations were developed in close collaboration with the MoH and other stakeholders, and a plan for filling the gaps are being developed and implemented.